“Self-harm and suicidal thoughts are a troubling part of many mental illnesses, but for those struggling with borderline personality disorder (BPD), the risk is extreme. In fact, self-harm and suicide attempts are so prevalent in BPD that it is the only mental disorder that includes such behaviours as part of its diagnostic criteria.

Suicide deaths range between 8-10%. This rate is 50 times greater than that found in the general population.”

************

Imagine the most intense feelings you have ever had to date – losing a family member, an intense argument with your partner, falling in love for the first time, holding your newborn child in your arms. These extremes are a pretty good reflection of the intensity of emotions a person with BPD – borderline personality disorder – feels on a daily basis. And when we fight with a partner, or fall in love – imagine those extremes, multiplied by ten. It’s fucking exhausting, and it’s always followed by a crushing self-hatred and desire for self-annihilation.

I have BPD. When I tell people about BPD, there are typically two responses: “Have you talked to a professional? A therapist?”; or, “Are you taking antidepressants? Maybe try another one?” Before you read on: I’ve done both and I’ve tried practically everything that is accessible to me. BPD isn’t a mood disorder any cocktail of drugs can solve – it’s a personality disorder, the same broad family of disorders as psychopathy and sociopathy – and I doubt anyone would suggest a psychopath take antidepressants. BPD is also stigmatized amongst psychologists – it’s much beyond the capabilities of most therapists, and we make for notoriously taxing patients even for the most seasoned professionals. If you look up psychologists in your area, check to see how many take on BPD patients. The percentage is pretty slim, and the fees exorbitantly high.

According to a slew of fMRI studies, BPD patients have a brain that is fundamentally wired wrong. There’s both “nature” and “nurture” behind the development of BPD – with research suggesting that 40% to 60% of the risk can be attributed to genetic abnormalities. These abnormalities appear to affect the brain pathways responsible for emotion stimulus processing, impulse control, perception, and reasoning. But we still know little about the brain today – it’s a complex machine that science has not yet parsed.

I was diagnosed with BPD two years ago, although the symptoms have been apparent for a much, much longer time. I remember only the most vivid vignettes: At age seven, a frustration with daily piano practice led to an intense rage that consumed me, stumbling to my mother saying: ‘I want to destroy the piano, burn the house, and kill you.’ At age nine, a disagreement with a friend on a sleepover (the origins of that disagreement now completely forgotten) pushed me into a seemingly bottomless pit of despair, where the only relief came from digging my fingernails into my thighs and scratching until the skin broke. My bewildered friend was sitting opposite me, consoled by my slightly less bewildered mother who had seen some of this rage before. And when I started university and visited Taiwan during spring break, a throwaway comment from a family friend telling me I “needed to lose weight” prompted a bout of anorexia. I calculated my caloric intake so I would have a net daily deficit of 600kcal, and stopped menstruating for two years. Some sort of twisted self-discipline predicated on self-hatred.

I’m unable to control these emotions in the moment, although my rational side is well aware that my reactions are completely unwarranted. At so many points of my life, I wished I had a terminal physical illness instead, so at the very least people could understand what I was going through, and I wouldn’t be afraid to talk about it.

For a seemingly endless time, I felt utter helplessness. I didn’t know how much to tell anyone, or how to get close to people – I believed I was broken, so I couldn’t trust my emotions. If I got too close to people, and felt comfortable letting my guard down, I ended up hurting those I loved most. A boyfriend would witness one of my breakdowns – that I cannot control – and inevitably leave me. I believed I ruined everything, which just drives a vicious cycle where I have a crippling fear of real or imagined abandonment. During my most unhinged periods, being left out of a party invitation led to cutting and a trip to the ER; after coming home from a hike where my texts went unanswered (there was no signal in the mountains), my boyfriend would find me collapsed in a corner with frostbite – as a less visible alternative to cutting, I would sometimes hold ice cubes in my hand until my hands went numb and tingled for the next few days.

BPD is often confused with bipolar because both involve extreme mood swings, but the two are not the same. Bipolar patients cycle through mania and depression between days, weeks or months, but there are typically moments of stability between mania and depression where they can function pretty normally and maintain in-depth relationships. That’s a stability I don’t have – my mood swings are highly reactive to interpersonal triggers, and it can happen at any and all times. I don’t think I’ve ever felt what normal is, nor understood what constitutes a “normal” physical reaction – if it weren’t self-harm, it would be the abuse of one substance or another, or reckless driving, spending, and sexual promiscuity.

I can feel the extreme emotions building up. It’s like a stomach ache – you know you’d need the bathroom in ten minutes, but you can’t just suppress the pain. I’m unable to “chill”, or “smile and be happy” – my rational mind knows I am overreacting, but I cannot suppress the emotions. And during a breakdown, when the emotions completely boil over, I have an out-of-body experience. I feel disassociated from my body – imagine a hit of ketamine, but your brain is still telling you to hurt (and if you hurt enough, kill) yourself. I remember excusing myself from work one afternoon, walking back home in this disassociated state. I passed a construction site, spotted a screwdriver on the ground, and it took every effort for me to not grab it and stab out my eyeballs. These hallucinations are always violent, always graphic, and always self-harm. I have a tendency to go through my contacts and block everyone before these breakdowns happen – so the dark bits don’t leak out over text. Images of slitting my throat, dismembered limbs, and the carcass rotting in my tiny, 150 square feet apartment. When these images come up, there’s not much I – or anyone else – can do. I lie in bed so that I don’t go into the kitchen for a knife.

The irrationality of BPD really fucks with me, because my mind has not failed me in any other aspects of life. For the first seventeen years of my life, I’ve been known as the overachiever – I won a scholarship to study pure mathematics, and switched to linguistics and graduated from one of the best universities in the world before I was of legal drinking age. I was a member of the Triple Nine Society until I let my membership lapse (if MENSA represented the 98th percentile of the world’s IQ, Triple Nine represented the top 99.9th percentile). I sold out from academia and charged my way into a high-octane investment banking job in New York. Two years later, I was headhunted to the idyllic tax haven island of Bermuda, where (mostly middle-aged) expats were furnished with a cushy budget for a country club membership, a boat, and access to the company private jet.

The problem is that my brain completely melts down once boredom settles in. It happened for the first time two years ago, in Bermuda, when my emotional extremes became unmanageable in frequency and scale, and breakdown followed breakdown. After a particularly bad breakup, I arrived home after a good night out with friends, and sharpened a knife to cut my arm. It went too deep, I got stitches at the hospital, and was placed on “suicide watch” for three months. People at work were not aware until I finally sat colleagues down, one by one, to ask for help. I got diagnosed with BPD, and started on a course of antidepressants that were largely useless.

I tried to find ways to regulate my emotion without cutting. Most of these involve significant risk or physical exertion, and read like a list of activities most hated by life insurance companies: solo backpacking through Somalia, scuba diving kilometers into underwater caves, swimming for hours on end in 12C water without a wetsuit. All of these activities require full engagement of the senses – a sort of forced meditation where a loss of focus could very well spell death. I moved from Bermuda to Hong Kong in an attempt to push my brain out of its comfort zone again; when COVID hit, however, many of my emotion regulation outlets were also closed off. No travel, no open swimming pools (nor cold water), and no opportunities for technical diving – although Hong Kong Island is surrounded by the ocean on all sides, there are no underwater caves nor dive sites deeper than 30m accessible by commercial boats.

I’m slowly emerging from another rough patch of BPD that has started since May. Two weeks after my 27th birthday, I was hospitalised for an antidepressant overdose – the result of another out-of-body breakdown, so I’m not exactly sure if it should count as a suicide attempt. I think I only wanted to feel better, but I’m not sure.

Perhaps “recovery” is the wrong word – since I’ll always live with BPD – but it’s taken me two years of reconciliation after my diagnosis to get my current mindset. My emotions are not any more stable, but my physical reactions to them are. I’m starting to plan things more than six months out again – since my diagnosis, I’d struggled to think of any sort of future because I wasn’t sure if I’d still be alive after my next inevitable breakdown. That’s the real reason I’d chosen to leave finance, opting for a much more flexible job where I could hide away more easily when I have my next emergency. I feel like my life has been on pause for two years already – it’s high time to press restart, to hang on to the good things, by the skin of my teeth if I have to, and never fucking let go.

From a positive point of view, personality disorders are the most difficult mental challenge anyone could go through – if I can single-handedly “re-wire” my thoughts, then there really is not much else I can’t do. And yes, although I feel hopelessness and loneliness and emptiness ten times more than the next person, I am also capable of feeling ten times more hope, tenacity, courage, love. Those are the good things that never get reported, but those are the things that drive me to have some pretty diverse, exhilarating, stories-for-the-grandkids sort of passions. In any case, I choose to see it this way. I don’t have much other choice if I want to live, and I’ve decided very much that I want to.

I’m writing all of this down because there are people I still need to apologise to. People whom I’ve loved very deeply, in my own silly, broken, but limitless way – the same people whom I’ve also hurt by the fallout from my emotional extremes. I’m sorry I didn’t know how to tell you all of this, or even what to tell you. Every bit of pain I put you through – I know it cut me doubly deep. But I didn’t know how to stop it, and even now – although the sky looks a bit more blue – it will continue to be a struggle I’ll try very hard to handle on my own.

To the one person who’s graced my life when I needed it most – the silliest of pigs, the most business of geese – thank you. Thank you for letting me zoom around the house after you hid everything sharp, thank you for being much braver than I was during my breakdowns. Thank you for laying on the floor next to me when I collapsed with raw pain, and holding me when I most needed to be held. Thank you for crawling into the spare bed after I hid in the guest bedroom in shame, and hugging me when I most wanted to disappear. Thank you for not asking me questions, because I had no answers. Thank you for loving me when I didn’t know how to start loving myself. At least I think you did, and that’s enough.

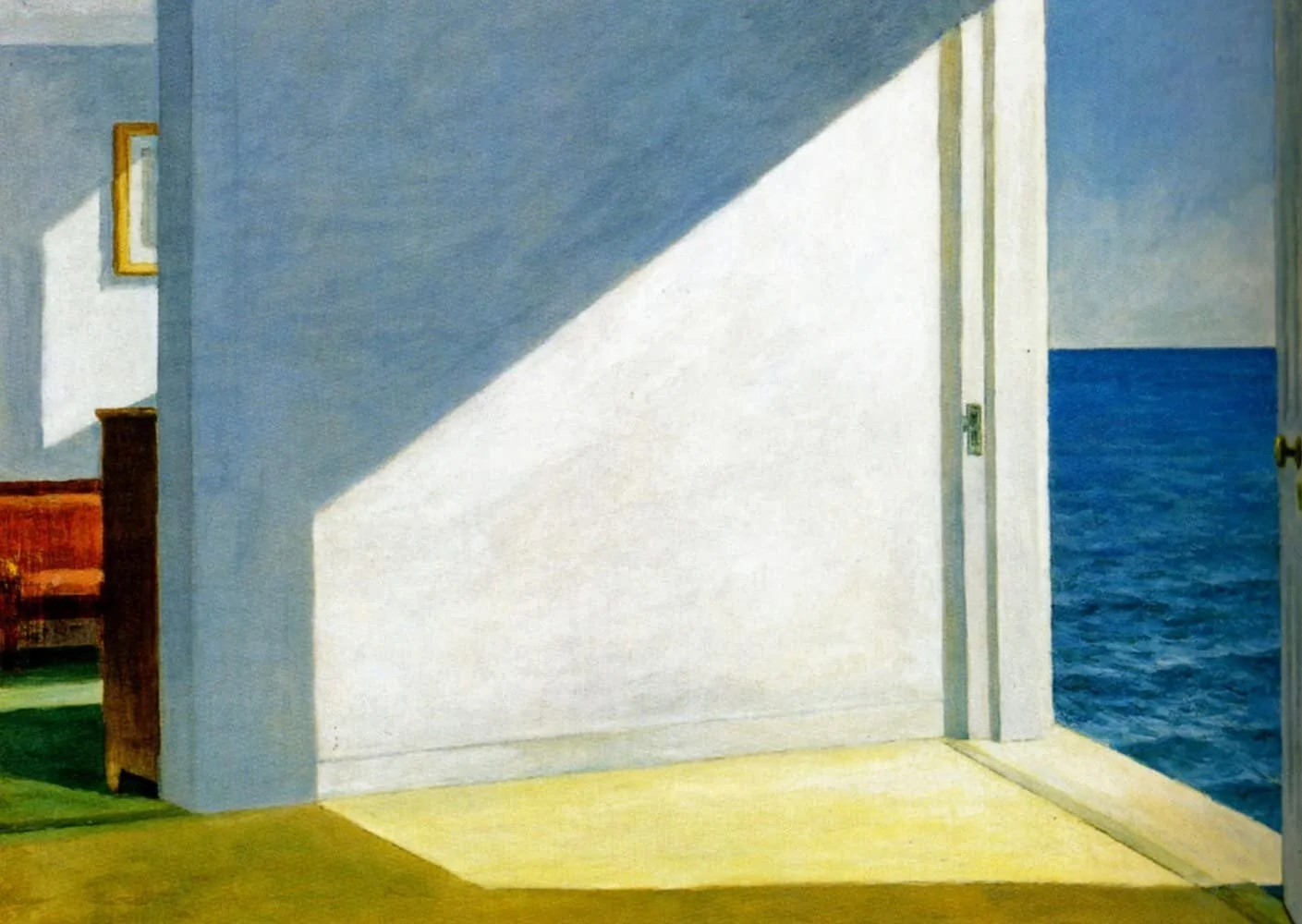

Rooms By the Sea, Edward Hopper (1951)